Fifth Sunday in Lent, year ‘B’: Not Just for Humans

Featured Contributor The Very Rev’d Peter Elliott, D.D

Is God’s saving work just for humans or for the whole of creation? On this last Sunday in Lent, the lectionary passages have been chosen to prepare the Christian community for the journey to the Cross. As you explore this week’s passages you can find an insistence that God is at work not just to save the humans but also the whole created order.

There is a progression of images from the first reading through to the gospel, from how God’s covenant is written in the human heart (Jeremiah) to an expression of penitence for sin (Psalm 51), to a mediation on the suffering of Jesus (Hebrews) and finally to an image drawn from nature of a seed dying in order to give new life (John).

This progression mirrors the way that many have come to a deeper appreciation of the interconnectedness of all life. It begins with a ‘heart’ moment—when our hearts break beholding the ways that human greed and pride have brought such violence upon God’s creation. We are led to express that heartbreak through words of contrition, praying for God’s mercy since we too participate in the destruction of this planet. We gain some solace in knowing that Jesus, in his own life, experienced deep anguish and pain and are comforted knowing that when we feel the pain of the earth’s destruction we are on holy ground. The gospel takes us to the natural world for an image of the generativity of change—how a dying grain is the energy of new life.

-

These words are addressed to a people in exile, far from home and bereft of hope. From a book filled with warnings and lament, this passage comes from a section of Jeremiah known as the Book of Consolation. It offers a promise held out to the exiled people of Israel that a new covenant will be written not on tablets of stone but on the human heart.

This idea of God’s covenant being written in the human heart invites these exiled pilgrims to look within and find that God is already there. The intimacy between God and these exiled people is emphasized when the prophet recalls that the God has always been as their husband.

Now the presence of the Holy One is even closer, “they shall all know me.” It is a promise that has resonated through centuries for Jews and Christians alike. The indwelling of God in our hearts—our deepest selves is the root of spirituality. Spiritual practices invite us to slow down our inner thoughts and dialogues, focus on our breath and be aware of how God’s Spirit is already within us, at our core, in our hearts.

But if God’s covenant of faithfulness is written on the human heart, there is yet another way that we can experience it. In my work as a pastor, whenever I had a conversation with someone who claimed that they did not believe in God, I would ask them where, in their life, did they feel connected with something greater than themselves. Over and again, people told stories of being in the natural world, seeing sea and mountain and being overcome with feelings of awe and transcendence. “They shall all know me” Jeremiah proclaims. While of course God can be known in sacred spaces in the built environment, how much more, if knowledge of God is already in the human heart, can we experience the divine in wildness of earth.

After all, the covenant referred to in this passage, the law given to Moses on Sinai was given to a people in the wilderness as they searched for the promised land. That covenant helped to form the people into a community of respect and dignity in relationship with God.

But this was not the first covenant God made. God’s very first covenant in Hebrew scripture was with Noah after the flood and it was not just for the human community but to all of nature, (Hochstein) “I now establish My covenant with you and your offspring after you, and with every living thing that is with you—birds, cattle, and every wild beast as well—all that have come out of the ark, every living thing on earth.” (Genesis 9:9) What would it mean for that covenant to be written on our hearts—that God will not destroy the earth—and so our care of the planet is not simply a moral obligation, it is paying attention to what has been written deep into our very selves.

-

On this last Sunday in Lent, the lectionary returns us to the Psalm appointed for Ash Wednesday. The historical background for Psalm 51 is the story of David’s rape of Bathsheba, the wife of one of his military generals who he then has her husband, Uriah, killed in battle. Confronted with what he has done, David’s only words are, “I have sinned against the Lord” (2 Sam 12:13). For centuries Christians and Jews have read Psalm 51 as the rest of David’s confession of sin and his plea for forgiveness.

Beginning in verses 1-2 there are four pleas to God: “have mercy, blot out, wash me, cleanse me” from “my transgressions,” “my iniquity,” and “my sin.” Transgressions, iniquity, and sin are the most common words used in the Hebrew Bible to describe acts committed against God and humanity. Each has a root meaning: “transgression” means “to go against, to rebel”; “iniquity” means “to bend, to twist”; and “sin” means “to miss a mark or goal”.

The psalmist prays for God’s “steadfast love (hesed) “and “abundant mercy (raham)”. God’s mercy is tied closely to the concept of “womb love,” the love a mother feels for her yet-to-be-born child. References to God’s steadfast love occur no less than one hundred times in the book of Psalms, and references to God’s mercy (compassion) occur no less than twenty-two times (deClaissé-Walford). The portion of the Psalm appointed ends with asking God to create a new heart and renew a right spirit. The Psalmist asks for the joy of God’s saving help again and be sustained with God’s bountiful Spirit.(Webb)

On Ash Wednesday, recitation of this Psalm preceded the litany of penitence which, while acknowledging the reality of individual sin goes on to identify the areas where we participate in social sin:

Blindness to human need and suffering

Indifference to injustice and cruelty

Prejudice and contempt towards those who differ from us

Waste and pollution of God’s creation and lack of concern for those who come after us.

Broadening the scope of penitence from individual sin to include corporate sin is important especially in a time when religion has become privatized, and morality is narrowly defined in personal terms. New hearts and new spirits are needed to face the social sins that beset us. God’s promise of writing a covenant on the human heart gives hope that the resources needed for us to change are already within us, the hope of God’s saving help is not remote but intimate.

-

To unpack this short lection, one needs to appreciate the way that the High Priest

functioned in the Jerusalem temple in Jesus’ time. The letter to the Hebrews, thought to be originally a sermon, has, as its purpose to establish Jesus’ identity as the one who brings healing to creation using, as a metaphor, the temple worship system of sacrifice. (Mundhal)

Theologian James Alison, reconstructing the liturgy of temple worship on the Day of Atonement provides insight into the high priest’s role in these liturgies: it is summarized below with a link to an online article in the sources and resources section. here. What’s important to note is that the sacrifices offered by the high priest are not only for the human community but for the whole of creation.

At the Atonement Festival—an ancient Jewish liturgy in the First Temple, the high priest would go into the Holy of Holies and sacrifice a bull or calf in expiation for his own sins and don a white robe-- the robe of an angel.

From that point he would cease to be a human being and would become the angel, one of whose names was “the Son of God”.

In the Holy of Holies, the priest would take one of two goats – a goat which was the Lord, and a goat which was Azazel (the “devil”), sacrifice the first goat to the LORD; and sprinkle the Mercy Seat---- a microcosm of creation-- a place that only the high priest was allowed to enter.

The rite of atonement was about the Creator emerging from the Holy of Holies to set people free from their impurities, sins, and transgressions. It’s not that the priest sacrifices something placate the deity; rather it is God who emerges from the Holy of Holies dressed in white to restore creation, out of love in order to allow creation to flow.

The Holy of Holies symbolised “the first day” –before time, before creation was brought into being.

The priest then came to the Temple Veil made of very rich material, representing the material world. The high priest would don a robe made of the same material as the Veil, to demonstrate God coming forth and entering into the world of creation to undo the way humans had snarled it up. This is God taking the initiative to break through for us.

Early Christians who wrote the New Testament understood clearly that Jesus was the authentic high priest, who was restoring the eternal covenant that had been established between God and Noah; Jesus was acting this out quite deliberately.

The text from Hebrews makes clear how Jesus is fulfilling the role of High Priest. This passage emphasizes the humanity of Jesus, that he too “offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission.” If high priests can be compassionate and humble, Jesus is even more so because he is the very essence of God who is compassionate, humble, slow of anger and of great mercy. His loud cries and tears are powerful signs that Jesus is fully human.

Ecological theologian Norman Wirzba points wisdom from within the Orthodox tradition: “According to the Orthodox view, what a priestly role (not necessarily a priest leading worship) does today is ‘lift our hearts’ to the place of heaven so that heavenly life can transform life on Earth here and now. Heaven is not a far-away place, but rather the transformation of every place so that the glory and grace of God are fully evident. When in priestly motion we lift our hearts to God, what we are doing is giving ourselves and the whole world to the new creation, the ‘new heaven and earth’ (Rev. 21:1) so that our interdependent need can be appreciated as blessing.”

Our shared priesthood in seeking eco-justice, then, expresses our prayer and action toward ending our arrogant exile from creation, ensuring the wholeness and peace that is Sabbath delight. (Mundhal)

-

Biblical commentator Dong Hyeon Jeong, a Professor of New Testament interpretation focusses on the ‘vegetal’ imagery at the heart of this passage, “unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” Here is a summary of his interpretation, access to the full article in the sources and resources:

We learn from the vegetal life cycle the importance of accepting decay or death.

Plants teach us that decay/death is not the end: leaves grow during spring, flowers blossom in summer, leaves fall in the autumn, slumber through winter, rising again in spring.

Plants teach us about resurrection. The Gospel of John illustrates “the inseparability of the human, the nonhuman, and the divine and as such the divinity of the nonhuman no less than the human.” (Stephen D Moore)

Like many other communities during the first century CE, the Johannine community reflected through the lens of the vegetal because of their agrarian milieu. For example, to lose one’s life is like a grain falling down on the earth, dying, sprouting into life, and bearing much fruit (verse 25).

Moreover, the plants probably helped them understand death in this life is not the end. Losing one’s life for the gospel is not a call for meaningless sacrifice or abuse. Rather, it is a reminder to “come and see” (John 1:39) from God’s creation that resurrection is vegetal.

We live and die in Christ because, like the plants, we believe in Christ’s promise of renewed life—eternal life, or ‘the great reality’—another way to translate John’s phrase ‘eternal life.’

Andrew Prior writes, “We have to let go of our small vision of life and entrust ourselves to a much larger reality.” This whole section of John’s gospel invites its hearers into a vision of the great reality, where the whole human family is drawn into one in Christ. A great reality where voices from heaven are heard. A great reality where the losing of life is an opening into a deeper, more generative gift.

Brother Curtis Almquist of the Society of St. John the Evangelist writes this, “Jesus said, “unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it will not bear fruit.” We’re to be fruitful. Something will need to die for us to be fruitful: some image of ourselves, some impression, decision, resolution, privilege, or fear. It’s going to get in the way of what Jesus calls “abundant life.” Let it go, surrender it, let it die.

Preaching and Teaching Ideas

Seasons, Seeds and Forests

The calendar of the church year is a product of the northern hemisphere. The three Christian major feasts—Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost—correspond closely to the solar calendar: Christmas, near the winter solstice, Easter near the spring equinox and Pentecost just after the summer solstice. For Christians in the northern hemisphere these feasts offer a meaningful way to connect our experiences of the earth’s cosmic voyage with the Christian story. On this the last Sunday in Lent, we remember that this season’s name is a shortened form of the Old English word lencten, meaning “spring season”. As the days and hours of light have lengthened you may have seen some plants shooting up through the soil and trees beginning to green up. These signs of regeneration take us to the promise of Easter for which we have been preparing, and to the natural rhythms of earth.

In today’s gospel, Jesus uses a seed to illustrate why it is necessary for him to die. “... unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit. Those who love their life lose it, and those who hate their life in this world will keep it for eternal life.” Jesus’ “parable” assumes ancient ideas that with the loss of their original form seeds ceased to be what they were and died. Even though we understand the growth process differently, the image still conveys power.

Poet and environmental activist Wendell Berry writing about forests says, “where the creation is yet fully alive and continuous and self-enriching, whatever dies enters directly into the life of the living ...” Norman Wirzba suggests, “Rather than viewing life as a possession, one inspired by Christ understands that life is a gift to be received and given again...All attempts to secure life from within or to withhold oneself from the offering that is the movement of life, will amount to life’s loss.” This is why Jesus says, “Those who love their life will lose it” Real life is expenditure.

As the church moves towards Holy Week and Easter, we need look no further to the change that the seasons bring to learn the importance of self-giving love. Sallie McFague writes about this: “The “way” of Jesus, the geography of the life he calls us to, is rather like an old-growth forest – marvelous, muddled, and messy. It works by symbiosis – living off one another. Nothing in an old-growth forest can go it alone; nothing could survive by itself; everything in the forest is interrelated and interdependent: all flora and fauna eat from, live from, the others.

The recognition that we own nothing, that we depend utterly on other life forms and natural processes, is the first step in our “rebirth” to a life of self-emptying love for others, a move from self-centeredness to reality-centeredness.”

Sources and Resources

The Working Preacher site has many good resources.

Rabbi Avital Hochstein’s work on the first covenant with Noah is a wonderful read.

For more background on worship in the Jerusalem temple see Margaret Barker’s books Temple Theology: An Introduction London, SPCK, 2004 and Temple Mysticism: An Introduction. London, SPCK, 2011.

The best introduction to the work of James Alison is Knowing Jesus. London: SPCK, 1998.

There is a brilliant article on John 12, Chapter 7 A Spirituality of the Paschal Mystery in Ronald Rolheiser’s The Holy Longing: The Search for a Christian Spirituality (Toronto: Doubleday, 1999)

James Conlon’s At the Edge of our Longing: Unspoken Hunger for Sacredness and Depth (Ottawa: Novalis, 2004) is filled with stories and quotes supporting ecological justice.

Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Commentary on Psalm 51:1-10

Dong Hyeon Jeong, Commentary on John 12:20-33

Stephen D. Moore, “What a (Sometimes Inanimate) Divine Animal and Plant Has to Teach Us about Being Human,” in Gospel Jesuses and Other Nonhumans: Biblical Criticism Post-Poststructuralism (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2017), 126.

Andrew Prior “Protons Neutrons and Electrons”

Curtis Almquist, “Dying to Live”

Wirzba, Norman. Food and Faith, Cambridge, 2011

Sallie McFague, Earth Economy: A spirituality of Limits

James Alison, Some Thoughts on Atonement

Elizabeth Webb, Commentary on Psalm 51:1-12

Tom Mundahl, Ending Our Exile from Creation

Author Bio

Peter Elliott is a priest in the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster. In 2019, he retired after serving as Dean of Christ Church Cathedral on the unceded and traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Peter currently works as a consultant and coach in private practice, is adjunct faculty at Vancouver School of Theology and is the co-host of the podcast the Gospel of Musical Theatre. https://gospelofmt.podbean.com

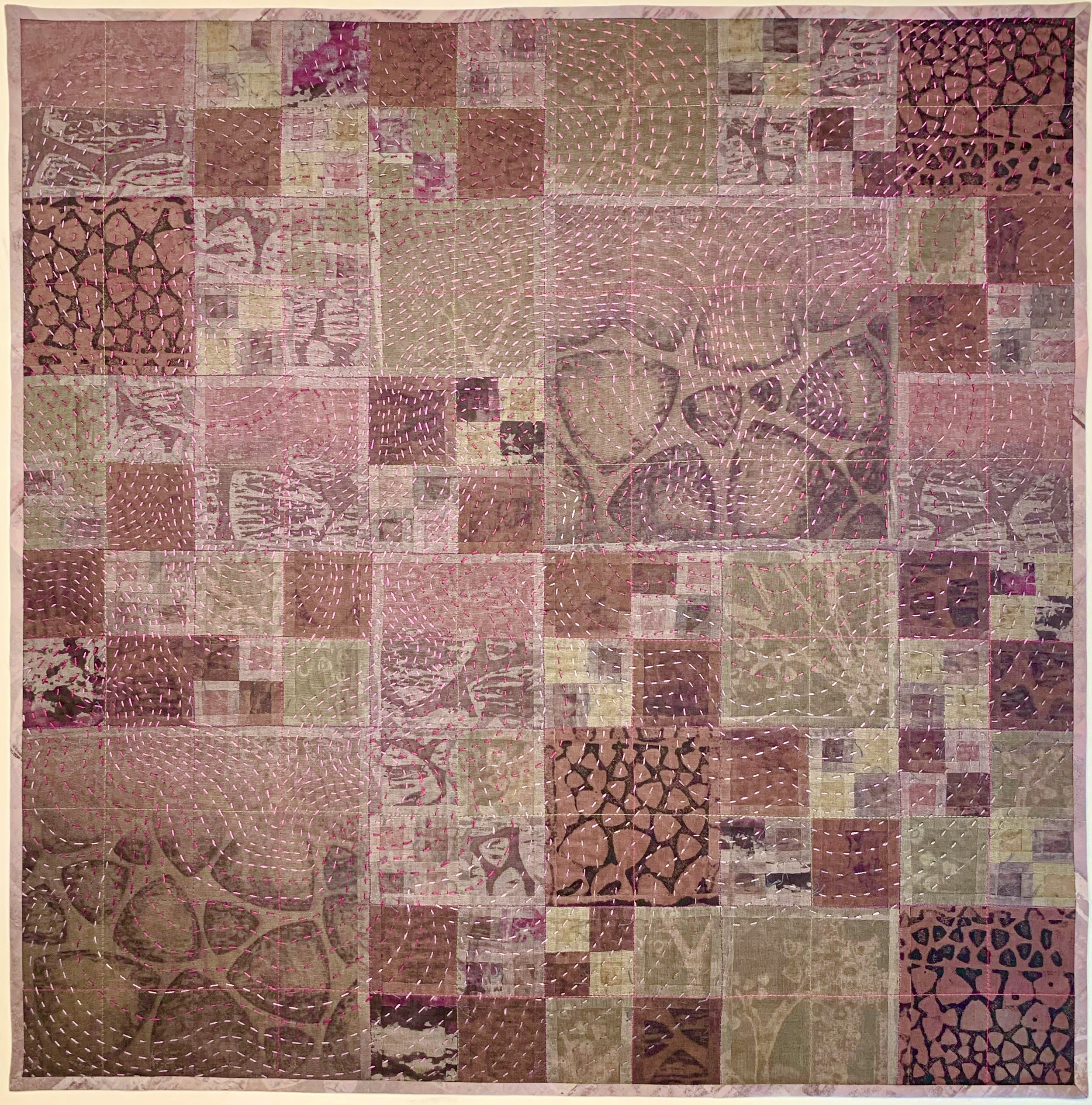

Featured image Soul Map is by Vancouver liturgical textile artist Thomas Roach http://www.thomasroach.ca/